La suite sur le forum : http://www.knightwoodoak.com/t2467-breeding-terms-explained#64150

Recapitulation

To those for whom it is written, however, a summation of the total effects of inbreeding, and to a modified degree that of line breeding, follows.

All characteristics both good and bad exist in various degrees in different dogs. One wishes in his matings to secure and retain the desirable characteristics, and it is easily demonstrable that this can best be accomplished by inbreeding and, to a lesser degree, by line breeding. It is also easy to show that, by using the same methods of breeding, the lowest intensity of undesirable characteristics is attainable. Results are entirely dependent upon SELECTION, remembering that

"Physical compensation is the foundation rock upon which all enduring worth must be built".

Inbred - Father/Daughter, Mother/Son, Full brother/Sister.

Linebreeding - As long as the common ancestors are within the first 3 generations but in saying that the degree would depend on how many times the common ancestor/line appears in those 3 generations.

Outcross - With our breeding we class anything with no common ancestors within the first 3 generations as an outcross.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linebreeding

http://www.rhiannon-cavaliers.com/linebreeding.htm

http://bowlingsite.mcf.com/genetics/inbreeding.html

Bientôt une traduction ;)

Old Tyme breeder

The return of the British Bull breed.

Like a lot of great things in the world of today such as football, rugby, cricket or the Queensbury rules, the history of these great things are British responsibilities. The same applies to the majority of great working dogs, be they running dogs, herding dogs or bull breeds. Our history makes it our responsibility to maintain these breeds in their original guise.

Our brutal past was not only imposed on our animals, but was part of people’s everyday lives. Whether a bare knuckle boxer, street kid or trader, life was hard and a step up the ladder only came from continual battles. Disease was rife and food was hard to come by, especially for the working classes.

The truth of the matter is when animals, including humans are faced with such adversities a certain mentality was undertaken, the survival of the fittest mentality; this included the live stock that shared our lives. The horses that could not perform their tasks were used for meat. Dogs that were unable to put food on the table or provide protection were disposed of.

These times produced hard people and the feelings of animals took second place to people’s welfare. Cheap food was achieved by the use of hunting animals, whether it is sight hounds, bull breed or mastiff types bringing home the bacon. Dogs were pitted against each other to achieve monetary gain for the owner and the gambling crowds.

This is not intended to be a history lesson, more to show the intense struggle the breeds have endured through the centuries and therefore highlight our present responsibility to them. These struggles gave us various types of dog that excelled at their given task. Over the years these dogs became set to type, their mindset and conformation was of the ultimate construction for the task.

For the bull, bear, and dog pit breeds, size and construction varied although to the untrained eye they are very similar. These different types should be studied by breed enthusiasts, and the subtle differences taken into account. Only then can we continue to breed and reproduce true replicas of yesterday’s canine gladiators.

The majority of bull breeds seen at K.C shows in the U.K are an untrue representation of the working dogs of the past, created by a misunderstanding of what body form a gladiator requires in order to stay the distance in his battles. These people do not understand the physical make up required for being able to bring these canines up to the physical fitness standards required for their original task, as most show bred stock lack the correct tools to achieve this state of fitness.

The K.C standards of these breeds are all well and good, but leave to much room for interpretation and exaggeration from the breeders fashion lead preferences.

It is true that most dogs today will never face such hard conditions again, nor should they, but the body structure they have been graced with and the unstoppable mental attitude processed by Bull breeds of all types should be protected, especially in the country of their origin.

I for one find bull breeds the most amazing creatures ever to have graced this world and the suffering of their past should be honoured by the retention of their greatest assets, their body and minds!

The future of our breeds needs protecting and education of the public is a vitally important. Shows, field trials, seminars and books with functional attributes being the focus are a way to achieve a brighter future for the modern bull breed, much good work is already being done but much more also needs to be done.

The breeds do have athletic shows to attend which are growing in size, but they are few and far between.

We need to come together and strike while the iron is hot to promote the return of the true British bull breed. The building blocks are there and it’s time to pick them up and build!

Here’s to the future, Neil

Sherlock.

Interesting article; black hair follicular dysplasia

Revised: October 30, 2001.

related terms: black hair follicular dysplasia

What is follicular dysplasia?

Follicular dysplasias are a group of syndromes which have in common abnormal hair loss and changes in coat quality. Hair loss starts at an early age and progresses very slowly. The changes are consistent in the different breeds affected (see below), suggesting a genetic connection.

Black hair follicular dysplasia is a rare inherited disorder that is seen in mixed-breed and purebred dogs. Hair loss occurs at a very early age in black areas on black, or black and white dogs.

How is follicular dysplasia inherited?

Black hair follicular dysplasia is believed to be inherited as an autosomal recessive trait. The modes of inheritance for other follicular dysplasias are unknown.

What breeds are affected by follicular dysplasia?

Follicular dysplasia:

Doberman pinscher - Hair loss starts slowly in the flank areas at 1 to 2 years of age, and progresses very slowly to the back and sides.

Siberian husky and malamute - At 3 to 4 months of age there is a loss of primary hairs on the dog's trunk, and the undercoat becomes crimped and reddish in colour. Clipped hair does not regrow.

Airedale terrier, boxer, English bulldog, Staffordshire terrier - Hair loss starts at 2 to 4 years of age and occurs on the back and sides in a saddle-like pattern. Sometimes the hair regrows and is lost again in a cyclical manner.

Portuguese water dog, Irish water spaniel, curly-coated retriever - Hair loss is first noticed at 2 to 4 years over the back, and spreads slowly to most of the trunk.

Other breeds affected by follicular dysplasia include the Chesapeake Bay retriever, English springer spaniel, German short-haired and wire-haired pointer, and rottweiler.

Black hair follicular dysplasia: mixed breed dogs, and purebred dogs of the following breeds: American cocker spaniel, basset hound, bearded collie, beagle, dachshund, Gordon setter, papillon, pointer, saluki, schipperke. The coat is normal at birth, but by 4 weeks or so, pups start to have abnormalities in the black parts of their haircoat. There is progressive hair loss until all black hairs are lost.

For many breeds and many disorders, the studies to determine the mode of inheritance or the frequency in the breed have not been carried out, or are inconclusive.

What does follicular dysplasia mean to your dog & you?

In most cases, the coat changes are very slowly progressive and permanent, and have little effect on your dog's health. There may be an increased susceptibility to bacterial infections. The dryness and scaliness of the coat can be treated symptomatically (see below).

How is follicular dysplasia diagnosed?

In black hair follicular dysplasia, the early onset and typical pattern of hair loss (black areas only) make diagnosis straightforward. For other follicular dysplasias, endocrine causes of hair loss must be considered. Your veterinarian will take a skin biopsy from your dog, which will show changes typical of follicular dysplasia. This is a simple procedure done with local anesthetic, in which your veterinarian removes a small sample of your dog's skin for examination by a veterinary pathologist. The biopsy will show changes in the skin consistent with this condition.

How is follicular dysplasia treated?

Generally the coat changes are permanent. Your veterinarian will likely suggest symptomatic treatment, such as shampoos and fatty acid supplements, for dry scaly skin. Skin infections that may develop are treated with antibiotics.

Breeding advice

It is preferable not to breed affected animals.

FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THIS DISORDER, PLEASE SEE YOUR VETERINARIAN.

Resources

Scott, D.W., Miller, W.H., Griffin, C.E. 1995. Muller and Kirk's Small Animal Dermatology. pp 773, 780. W.B. Saunders Co., Toronto.

Copyright © 1998 Canine Inherited Disorders Database. All rights reserved.

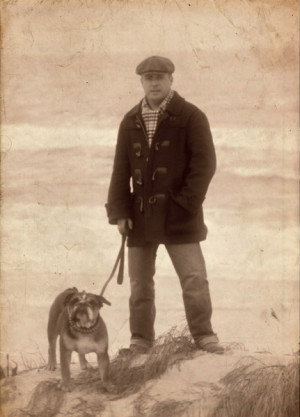

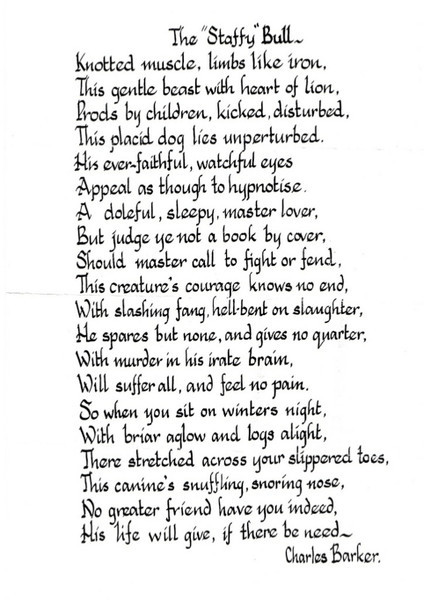

STAFFORDSHIRE BULL TERRIER

By PHIL DRABBLE.

Like most of the worthwhile things in life, a good Stafford is not attained without effort on the part of his owner. If he is thoroughly trained and well exercised, no dog could possibly be a more delightful companion. On the other hand, an untrained, under-

exercised Stafford can do more mischief in a few moments than any dog I know.

This is easily understood when it is realised that Staffords have been bred for more than a century for the sole purpose of dog-fighting. When bull-baiting finally ceased, about 1835, the men who worshipped at the shrine of the Game Dog transferred their devotion from the bull-ring to the dog pit. Dog-fighting had long been very popular and bulldogs had been crossed with various terriers to produce the combination of dauntless courage with agility and endurance which was even more necessary in the pit than the ring. At first, the resulting crossbreds, which must have been anything but uniform, were called "bull-and-terriers" and, as the best of them were used for breeding, a new breed was gradually evolved which became known as 'bull terriers." Some of these bull terriers took after their bulldog ancestors and were quite heavy "cloddy" dogs of up to 50 lbs in weight. Others, which took after the terriers, were only between 10 and 20 lbs. There was no "type", as the term is understood by modern dog-breeders. Men did not care what they looked like so long as they would fight; and, if they would not fight, they went in the water-butt no matter how good looking they were.

Between 1860 and 1870 these bull terriers were split into two camps. James Hinks, of Birmingham, who had always loved a game dog, produced a white strain which he registered at the Kennel Club as "English Bull Terriers". It is believed that they were produced by crossing the original bull terriers with Dalmatians, and much of their gameness was quickly sacrificed for looks, which was the only commodity paying dividends in the show ring. The original breed, which was still unspoilt by crossing with dogs which had not been bred for gameness, was now barred from the official title of Bull Terrier and it gradually became known as the Staffordshire Bull Terrier to distinguish it from the newer breed. The reason that Staffordshire was used as the qualifying term, to distinguish between the old and the new, was that the colliers and ironworkers of Staffordshire were so attached to dog-fighting that the sport became practically localised in the Midlands.

Half a century went by without the popularity of dog fighting waning, despite spasmodic brushes with the police. Nothing had been done to standardise any type, for courage and physical fitness were still the only things which mattered. Any dog which proved unusually successful in the pit was certain to be used as a sire irrespective of his looks and there was still a wide variation of types which have since become curiously localised. In the Walsall district it is common to find dogs of 34-38 lbs which are tall enough to convey a suggestion of whippet in their ancestry. My own theory of this is that a faint cross of bull terrier was sometimes used to impart endurance to whippets and it is possible that the offspring of one of these crosses displayed sufficient aptitude for fighting to have been crossed back to bull terriers, for agility in the pit is as necessary as courage. Only a few miles from Walsall, in the Darlaston district, the Staffords obviously favour their terrier forbears. They are much "finer" in the muzzle and obviously "terrier faced." They are smaller altogether and lighter boned, turning the scale at from 25-38 lbs, and occasionally] even lighter. The Darlaston men say all the others "must have been crossed with mastiff" and that "theirs" are the only real Staffords.

To confound them both, there is a third type to be found in the Cradley Heath area a few miles to the west. This time it is obvious that some members in the pedigree had more than a nodding acquaintance with a bulldog. Short, thick muzzle and broad skull, tremendous spring of ribs and breadth of chest, muscles which seem to be symbolic of power, everything combines to convey an impression of doggedness. This time agility has been sacrificed for strength and yet there is an unmistakable resemblance between all three types. The expression of the face is the same and the way the tail is carried drooping like a pump handle; the characteristic high-pitched staccato bark and the mincing springy walk, which emphasises the constant craving for action. Who can say that one type is "right" and the others "wrong"? Who can say that this dog is a "real" Stafford and that is not? Until very recent years, nobody minded very much so long as each was willing to give a good account in the pit. But that is changing now.

In 1935 it occurred to a band of owners that, as the police had become so extra-ordinarily fussy about dog-fighting since the Great War, it might be a good idea to arrange dog-shows as an alternative attraction. Accordingly, a schedule was drawn up to depict a scale of points for judging and the Kennel Club obliged by "recognising" the breed as the Staffordshire Bull Terrier.

It was natural that the men who drew up the scale of points should model their ideal from their own particular strains, which happened to be the "bulldoggy" type in favour in the Cradley Heath district. The result has been very far-reaching. Due to the publicity acquired from organised dog shows the popularity of Staffords has soared and their market value has been inflated in the same ratio. This attracted a new type of owner who is interested more in the value than the gameness of the breed, and who is loud in his assertion that the show type is "right" and that the show enthusiasts will "standardise" the breed and eradicate all which do not conform to the standard.

I feel very sorry about all this for I think it is a great pity to try to "breed out" all the types which do not conform to such an arbitrary standard. Fighting was the original purpose of the breed, yet all which do not waddle round the show ring without any display of fire are penalised. I have heard long arguments about which type is best for the pit. Some like the "reachey" dog, like the Walsall breed, because he can "fight down" on his adversary. Some like the stocky Cradley type because they are hard to knock off their feet. Some like the little terrier-like dogs which are so nippy and can do such damage by shaking. In the pit one triumphs today and another tomorrow. Despite the fact that failures were not given the opportunity to perpetuate their like, there were many good dogs of each type that there could have been nothing to choose for prowess. Yet the money to be by made by selling "pedigree" dogs is inducing owners not only to "standardise" to an arbitrary type but to exaggerate the points of that type, so that it appears more powerful by being thicker and lower to ground and bigger in skull than was any dog which fought in the pit.

This extraordinary variation in type of Staffords is by no means confined to physical appearance. All good Staffords are game, but some are essentially boisterous and rough while others are equally docile and gentle, both characteristics being passed on through strains as definitely as physical appearance. Two very famous dogs, which I happen to have known very well, exhibited these tendencies to a marked degree--Ch. Gentleman Jim and Great Bomber. Jim was all that his name implies, and generally speaking his offspring are tractable, intelligent and easily trained. Bomber on the other hand just could not keep still, was overflowing with boisterous friendliness and extremely headstrong. His type need an exceptionally firm (and occasionally heavy!) hand to control, whereas it is easy to hurt the gentler type's feelings and make them deeply offended with a few harsh words.

No dogs are physically tougher than Staffords, for they seem almost impervious to pain. I have seen my own bitch, which is "broken" to ferrets, go into the ferret pen to see what she can scrounge. One of the ferrets "pinned" her through the lip and hung on, which must have been pretty painful. Yet she didn't get annoyed or make any fuss but calmly came to find me to have it throttled off. It is this indifference to pain which makes them such peerless fighting dogs. Almost any dog will fight if he is winning, but it takes an exceptional dog to fight a long losing battle and then go back for more, when he has the chance not to; yet a good Stafford will go back so long as he can crawl across. Despite this the breed is not naturally pugnacious, and it is unusual for a Stafford to begin his first fight. He is either "set on" by someone or attacked and fights back in self defense. But once he (or she, for bitches will fight) has tried fighting there is nothing they would rather do. And that is why I advise no one but a real enthusiast to embark upon the ownership of one of these dogs. The man who wants a dog for a household pet, but who expects it to run loose and look after itself will soon regret his choice. I have known them run loose in the streets and play with other dogs for two or three years. But sooner or later they either get hurt playing or mixed up in someone else's quarrel and suddenly realise what fun they have missed. From that time forth they need no second invitation and they fight to kill. Neither water nor any of the usual remedies will part them and I have seen a dog fighting a collie twice his size in a canal, where the owner of the collie had thrown them to part them. But the terrier could not loose and they both very nearly drowned before we could get them out. And owners who are not enthusiastic are often averse to getting sufficiently mixed up in the bother to choke their dog off, which is the only effective way.

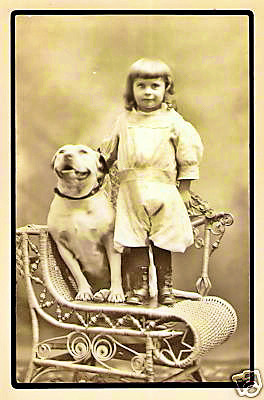

Anyone who is willing to take the necessary pains to train and exercise a potential handful of trouble will be amply rewarded by finding it far less onerous than he thought. He will get devotion undreamed of in lesser breeds-and "Stafford men" regard all other breeds as curs. He will get a dog which is a peerless companion for children, though it will be necessary to watch that he doesn't "help" too vigorously if his young master has a quarrel with a playmate. He will have a dog which is unbeatable on rats and will be game to have a go at any other quarry his master selects. Some Staffords have made very fine gun dogs but, oddly enough, a high proportion are gun-shy, though often not initially. My own bitch for instance, came shooting quite happily at the beginning of her first season. She gradually took a dislike to the gun and it almost seemed as if it wasn't the bang to which she objected but that she came to realise that something got killed when it went off and that my marksmanship wasn't so hot. Similarly many Staffords make fine water-dogs and I have seen them matched to beat spaniels and retrievers over a distance, but it is necessary to introduce them to water gradually and in warm weather, or they often will not take to it at all.

In a word, the Stafford is a dog of very exceptional character. Take great pains to develop it and direct it into useful channels and there is no breed in the world as good. Let it grow haphazard without training or care and you will have a villain whose only aim in life is to fight. "And to keep a fighting dog", they say, "you have to be a fighting man."

Standard Amendment - Staffordshire Bull Terrier

Standard Amendment

The joint meeting of Staffordshire Bull Terrier Specialist Clubs was held on Saturday, July 26th, 1952, at Birmingham, following the Staffordshire Bull Terrier Club's Championship Show.

La suite sur le forum ... http://www.knightwoodoak.com/t3357-standard-amendment#64145

;) ... La suite sur le forum ... http://www.knightwoodoak.com/t236-the-rellim-story-by-jack-miller#64129

The Old Original Standard

- England 1935 -

General Appearance

The Staffordshire Bull Terrier is a smooth-coated dog, standing about 15 to 18 inches high at the shoulder. He should give the impression of great strength for his size, and although muscular should be active and agile.

Head

Short, deep through, broad skull, very pronounced cheek muscles, distinct stop, short foreface, mouth level.

Ears

Rose, half prick and prick; these three to be preferred, full drop to be penalized.

Eyes Dark.

Neck Should be muscular and rather short.

Body Short back, deep brisket, light in loins with forelegs set rather wide apart to permit of chest development.

Front Legs Straight, feet well padded, to turn out a little and showing no weakness at pasterns.

Hind Legs Hindquarters well muscled, let down at hocks like a terrier.

Coat Short, smooth and close to skin.

Tail The tail should be of medium length tapering to a point and carried rather low; it should not curl much and may be compared with an old-fashioned pump handle.

Weight Dogs 28 to 38 lbs., Bitches 4 lbs. less.

Colour May be any shade of Brindle, Black, White, Fawn or Red, or any of these colours with White. Black and Tan and Liver not to be encouraged.

Faults to be Penalized Dudley nose, light or pink eyes (rims), tail too long or badly curled, badly undershot or overshot mouths.

Comment nous joindre

Iratxoak-Celtic Oak Farm

Siret : 532 057 767 00032

theoaks@live.fr

06 52 822 833